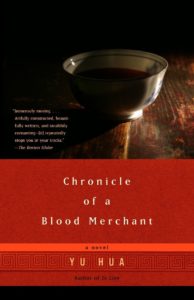

Review: Chronicle of A Blood Merchant

Chronicle of a Blood Merchant is the second book I have read by Yu Hua, and though perhaps not as moving as To Live, Chronicle shows, unequivocally, why Mr. Yu belongs to the upper echelon of China’s most celebrated contemporary writers.

The story of Xu Sanguan and his family (a wife and three kids) is, at first glance, simple and straightforward: a family’s struggle to go through life, staying together, no matter how hard their life becomes, all the while trying to keep their sense of honesty and decency intact.

Every time a tragedy strikes or the immediate need of money looms menacingly over the family, Xu Sanguan sells his blood for 35 yuan (a practice not so unusual in China). The blood is his life, it is not the sweat of work, but it is part of him, as he says, and he never sells it lightly. He does so to make ends meet, to pay a debt, to buy a decent meal for his family undernourished by famine, to save a life.

Every time he goes to the Hospital to sell his blood, Xu Sanguan does it without regret or fear for his life, for when the members of his family need him, he must do whatever he can to help them.

Though it covers several decades of Xu Sanguan’s life, Chronicle of a Blood Merchant is not as eventful and as entangled with China’s recent history as To Live. Mao’s China and its many tragic moments are embedded in the narrative, but they are never truly dealt with, in any depth at least. Readers with no previous knowledge of the Great Famine and the Cultural Revolution, for instance, will not find much enlightenment in here. Yet, they will understand the tragic effects of these events on ordinary Chinese families.

More like threatening shadows than actual characters, these historical sins serve the purpose of triggering a series of crises in Xu Sanguan’s family, hence the need for him to counter their catastrophic effects by selling his blood. Xu Sanguan recurrent sale of his own blood is at times a subtle, yet ferocious indictment of China’s politics under Mao, and the country’s failure to take care of its people, especially those on the lower scale of the economic spectrum.

But the book is not only about politics, but it is also mostly about life and especially the life of Chinese people, and more specifically of a Chinese family living in a small nondescript city. Yu Hua never shies away from showing the abject cruelty of people when their individuality becomes enmeshed into a righteous, vindictive mass of censors singling out some of their peers for alleged morally corrupted acts. The accused are, more often than not, just hapless victim (as it happens a few times throughout the book to Xu Sanguan and his family, and especially to Xu Yulan, his wife.)

Yu Hua’s characters and stories, however, are always complex and full of subtle nuances. This book is not an exception. There are no absolute heroes or absolute good people in this story, but men and women and their intricate bundle of faults and goodness, and their neverending struggle for life.

The story is also about generosity. The same people who once eagerly accused or shrugged off with mocking malice one of the characters are ready to give what they have to help the same person when he and his family are in truly desperate need.

There are also many reversals of fortune: bad times and tragedies eventually strike everyone, the accusers are suddenly in need, and need the help of those they were once mean to. But the moral strength of Xu Sanguan’s character shows the reader that these reversals are never lived with excessive schadenfreude (or at least not for long). A Confucian ethos informs the story. Xu Sanguan and his family believe that one must always strive to be kind and live a good life, which means never to seek revenge or refuse help, even to those we would have all the rights to do so.

The book has Yu Hua’s characteristic narrative style, controlled, non-judgemental, often slow-paced, and yet rich in nuances. He has a special gift for painting the grotesque attitude of the people, in the face of tragedy (of others), especially when these are representative of the elites, or the party (as it is the case of Li, the Blood Boss, at the Hospital, the one who decides who sells the blood or not, who gets the money and who doesn’t).

Overall Chronicle of a Blood Merchant is a great book, tragic and yet optimistic, positive in its outlook to life and family. And, in passing, a perfect companion for To Live.